News and Updates

Contact

Faculty of Social Science

Social Science Centre

Room 9438

Western University

T. 519-661-2053

F. 519-661-3868

E. social-science@uwo.ca

Links between brain and skeletal development offer new possibilities for understanding human evolution

December 16, 2022

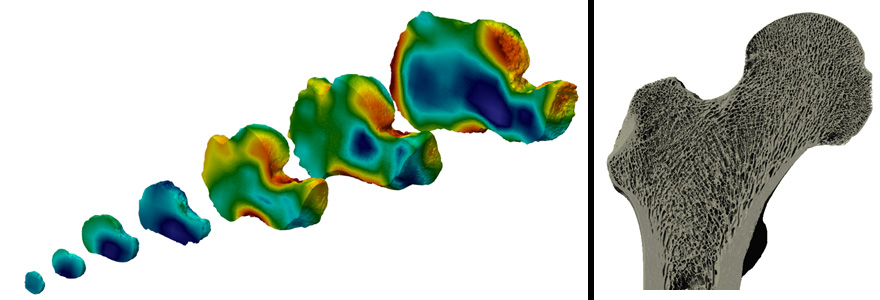

On left, digital models of bones showing age related changes in bone density in the human heel bone (calcaneus). On right, a digital model of the three dimensional structure of trabecular bone in the human hip. Both images created using Micro-CT scanning.

Story by Rob Rombouts

New research shows that brain development in humans and other primates is closely linked to skeletal development, a finding that creates completely new options for studying the evolution and development of the human brain.

“We know that a major factor in evolutionary change is the regulation of subtle differences in growth and development,” said Jay Stock, co-author on the paper, and professor of biological anthropology at Western. “Extending or shortening the ‘investment’ in different tissues can generate major differences between species.”

Modern humans develop much more slowly than other species, but this slower growth allows for the brain growth and development of more neural connections that define humans, such as learning languages and social behaviour, and building social networks.

A team of researchers, including Stock, compared the development of trabecular bone among humans, two species of apes: gorillas and chimpanzees, and one species of monkey, the Japanese macaque, to determine patterns of causation between neural development and skeletal development. Their research was recently published in PNAS.

“We have been studying trabecular bone, the spongy bone found predominantly in the ends of long bones, for many years,” said Stock. “The density, volume, and orientation of trabecular bone is known to relate to activity patterns in life, but we don’t know too much about its development.”

Jaap Saers, lead author of the study and a researcher at the University of Cambridge and Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands, said they were surprised to see that age-related changes in bone structure did not follow changes in body size, but rather corresponded to brain maturation.

“This connection seemed arbitrary at first, but we quickly realised that the brain of course controls the movement of the rest of the body,” said Saers. “These movements subject bones to different forces to which they adapt by adding more bone. This provides a causal mechanism linking the development of the brain to the development of locomotion, and, in turn, to the development of the skeleton.”

Based on this new understanding, scientists can interpret aspects of neural development from parts of the skeleton other than the skull. They can also learn more about parts of the body, such as the nervous system, that do not fossilize.

“Researchers have had a hard time studying neural development from the fossil record,” said Stock. “To understand brain growth, we needed to find relatively complete fossilized skulls, and ideally skulls that have not completed growth.”

“The close connections between brain development, locomotion, and bone development offer some exciting new ways to understand the evolution of some key human characteristics,” said Saers.

Examining bone growth and development in the fossils of human relatives will allow scientists to determine the age at which their infants were able to move around by themselves, and how quickly their brains and locomotor ability developed. They can also determine whether our fossil relatives used their upper limbs to climb trees or were more permanently tied to the ground at different stages of their development.

“This opens up completely new possibilities for studying the evolutionary history of our species,” said Saers.